The over-arching goal of audiologic rehabilitation is to enable persons with hearing-related problems and their communication partners to improve their quality of life and optimize participation in daily activities. With this in mind, I will discuss components of audiologic rehabilitation that can be used to improve the cognitive performance of patients with hearing loss.

(1) Signal Improvement

The most common way to achieve this goal is to improve auditory input using technology. Technology can make signals more audible and/or enhance signal clarity by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. Of course, improving auditory input helps people to hear and communicate better. An important bonus is that making it easier for a person to hear auditory input also has benefits for their cognitive performance and how well they can use the incoming auditory information. For all people, regardless of age and whether or not they have hearing loss, better quality auditory input can speed up cognitive processing and make it easier for listeners to attend to and remember the information that has been heard.

(2) Auditory Training on Communication Strategies

Apart from using technology to achieve the over-arching goal of rehabilitation, audiologists may provide training on communication strategies to increase awareness of and skill in using supportive context (e.g., clarifying the topic of conversation). The use of context is an effective way to compensate when it is hard to hear incoming auditory information. Audiologists should expect better cognitive performance when rehabilitation successfully combines technology and training.

(3) Memory Assessment

Did you know that existing audiologic tools can provide insights into how efficiently listeners are accessing and using incoming auditory information and mapping it to stored knowledge? Speech understanding always relies on mapping the incoming signal to stored knowledge. People who are older and/or hard of hearing may rely more on stored knowledge based on context (top-down processing) and less on sensory input (bottom-up processing). Also, depending on the situation, an individual may shift how much they use signal vs. context.

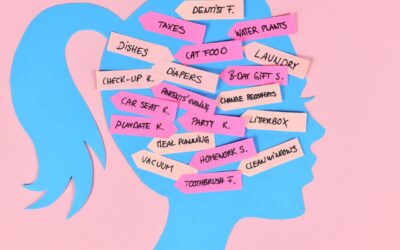

Memory is a key domain of cognitive processing that can vary with the quality of the signal and available contextual support. Ability to remember what was heard has important implications for listening in everyday life. If listeners are struggling to hear then what they hear will not stick so well in memory and they may not be able to remember something from early in a conversation by the end of a conversation.

Sherry Smith has published a number of research papers on the development of the WARRM (Word Auditory Recognition and Recall Measure). The most recent version of the WARRM is abbreviated so it would be feasible to use in the clinic (Smith et al., 2020). In the original research version of the WARRM, 100 words were used in a list, but the abbreviated version uses only 20 words. Well-known clinical word recognition test stimuli (e.g., NU6 items) were used to construct lists equated for difficulty. After each item, the listener repeats the target word, and these responses yield a typical word recognition score. The items are organized into recall sets. At the end of each recall set, the listener is asked to remember the target words in the set. The size of the set increases and a recall score is determined based on the largest number of words in a set that can be correctly remembered, crediting recall responses as correct if the listener correctly recalls an incorrectly recognized word.

People with mild hearing loss typically score close to 100% correct on word recognition, but as the number of words in a set increases, there are differences in the number of words they can recall. People with hearing loss remember fewer words than their age counterparts with good hearing and older adults with good hearing remember fewer words than younger people with good hearing. Memory is also reduced if the person is required to do a concurrent task.

Interestingly, in an analysis of the memory sub-test of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Dupuis et al., 2015), after accounting for accuracy of word recognition, memory was equivalent for people with and without hearing loss on the last word in the 5-item recall list, but there were differences in how well they recalled the earlier words in the list, even when the words had been repeated correctly. Hearing better is like using a stronger glue: the better a person hears, the longer words will stick in memory.

The WARRM test is not currently used clinically; however, the Repeat and Recall Test (RRT) is a similar but more complicated test that considers the effects of signal and contextual factors (Kuk et al., 2020, 2024). A shorter more clinically-friendly version of the RRT has been developed recently (Slugocki, et al., 2024). A RRT description and tutorial is available online (https://www.orca-us.info/en/research/rrt).

If you found this blog helpful, please share it on social media!

References

Dupuis, K., Pichora-Fuller, M.K., Marchuk, V., Chasteen, A., Singh, G. & Smith, S.L. (2015). Effects of hearing and vision impairments on performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 22(4), 413-427. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2014.968084

Kuk, F., Slugocki, C., & Korhonen, P. (2024). Characteristics of the quick repeat-recall test (Q-RRT). International journal of audiology, 63(7), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2023.2245969

Kuk, F., Slugocki, C., & Korhonen, P. (2020). Using the Repeat-Recall Test to Examine Factors Affecting Context Use. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 31(10), 771–780. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1719136

Slugocki, C., Kuk, F., & Korhonen, Petri1. (2024). Acoustic- versus intelligibility-based assessment of subjective listening difficulty measured with the Repeat-Recall Test. Ear & Hearing:10.1097/AUD.0000000000001575, PAP October 17, 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001575

Smith, S. L., Ryan, D. B., & Pichora-Fuller, M. K. (2020). Development of abbreviated versions of the Word Auditory Recognition and Recall Measure. Ear and Hearing, 41(6), 1483-1491. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000869