Tinnitus — the perception of sound without an external source — can profoundly affect daily life, often experienced as ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears. The most common type, subjective tinnitus, is usually linked to hearing loss without a clear medical cause. While the definition sounds simple, the reality is far more complex. Tinnitus is a multifaceted symptom, associated with a wide range of health conditions and capable of significantly impacting quality of life.

According to Statistics Canada, an estimated 9.2 million Canadian adults — nearly 37% of the population — reported tinnitus in the past year. About 7% said their symptoms were severe enough to interfere with communication, disrupt sleep, increase stress, lower mood, reduce work performance, and affect overall coping. For these individuals, the emotional burden can be as challenging as the sound itself.

What often goes unrecognized is how many factors influence the tinnitus experience. These include hearing changes, prolonged headphone use among young adults, natural aging of the auditory system, high stress, poor sleep, chronic health conditions (such as poorly managed hypertension), and reduced mental well-being. Tinnitus loudness or pitch can also change with jaw or neck issues or past injuries (somatosensory modulation) and can be further aggravated by lifestyle habits such as alcohol use or unprotected exposure to loud sounds.

In this blog, I’ll focus specifically on the connection between tinnitus and mental health. Psychological factors and tinnitus influence each other: stress, mood, and mental well-being can shape how tinnitus is perceived, while tinnitus itself can affect emotional health and daily functioning.

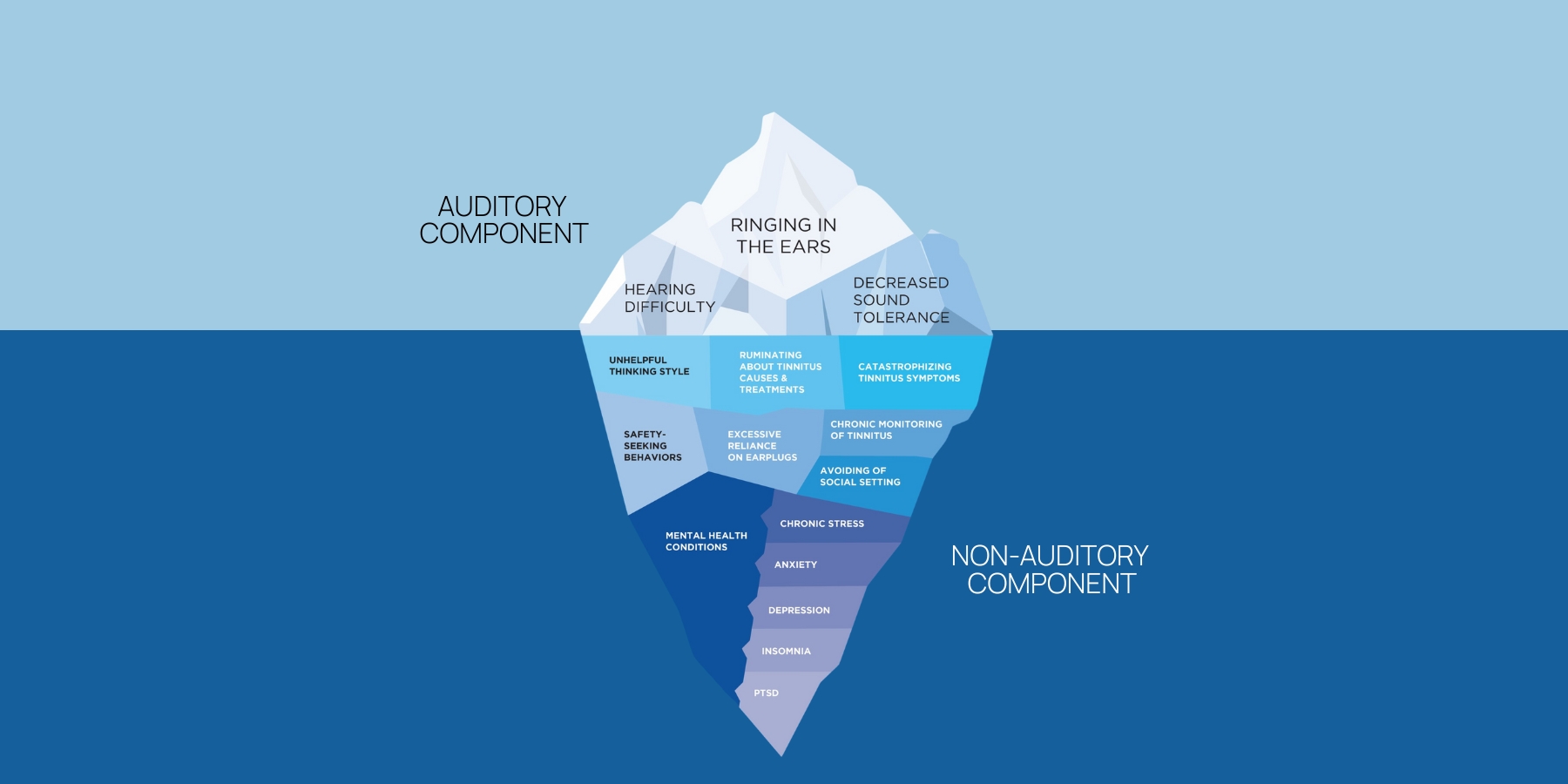

Looking Below the Surface: The Iceberg Model

The iceberg model offers a simple yet powerful way to explain why some patients find tinnitus more bothersome than others. Above the surface lies the tinnitus percept itself, along with hearing difficulty. Beneath the surface are a range of influencing factors — such as unhelpful thinking styles (e.g., catastrophizing tinnitus symptoms, ruminating about its causes), safety-seeking behaviours (e.g., constant monitoring of tinnitus, avoiding social settings), stress, anxiety, depression, poor sleep, and diminished overall well-being — that can amplify its severity. The visual of the iceberg helps patients connect the dots quickly, showing that their reaction to tinnitus is not only shaped by the sound they perceive but also by underlying emotional and health-related influences.

What makes the iceberg model powerful is how it shows that thoughts, feelings, and behaviours directly shape tinnitus perception. Two people can perceive the same sound very differently depending on what lies beneath the surface.

The Bidirectional Relationship

It’s tempting to think of tinnitus as simply causing distress. But the reality is more complex: unaddressed mental health conditions also influence how tinnitus is perceived.

Research consistently shows that:

- 30–40% of tinnitus patients experience anxiety disorders

- 20–30% experience depression

- 40–70% struggle with sleep disturbances, compared to just 10–15% in the general population

- Veterans face increased risk due to noise exposure and PTSD

This bidirectional relationship—often described as a “vicious cycle”—in which tinnitus intensifies psychological stress, and unaddressed mental health challenges, worries, and negative thinking, in turn, amplify tinnitus perception. Recognizing this pattern helps us intervene more effectively.

Spotting the Red Flags

Many patients believe that “curing” their tinnitus will solve everything. Often, the real driver of suffering lies in the emotional and cognitive reactions to the sound. Watch for signs such as:

- Catastrophizing the health threat caused by tinnitus

- Ruminating about what caused it and self-blaming

- Avoidance behaviours, such as skipping social activities, work, or hobbies, that disrupt everyday life

- Persistent sleep difficulties

- Noticeable mood changes or irritability

- Social withdrawal or relationship strain

These red flags suggest that mental health factors may be playing a larger role than patients realize.

A Three-Axis Framework for Assessment

To gain a comprehensive understanding of tinnitus symptoms, I recommend evaluating three key areas:

- Hearing Assessment – Begin with a detailed case history and a comprehensive audiological evaluation, including speech-in-noise testing and assessment of loudness discomfort levels (i.e., hyperacusis). Remember, up to 90% of people with tinnitus have some degree of hearing loss, whether clinically significant or subclinical (hidden hearing loss).

- Tinnitus Evaluation – Characterize the perceived tinnitus (quality, type, duration, triggers) and use clinical tools like the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS) to understand its impact on daily life, emotional well-being, and functional abilities.

- Mental Well-Being Screening – Even if it feels outside our comfort zone, simple clinical tools like the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) can help screen for emotional or behavioral difficulties.

Talking About Mental Health

Many hearing care professionals hesitate to raise mental health concerns, fearing it will be uncomfortable or outside their scope. But approaching these conversations with sensitivity and supportive language can help patients discuss tinnitus-related distress without stigma. Hearing care professionals can focus on cognitive, behavioral, and emotional well-being, while avoiding diagnostic labels, since they are not authorized to diagnose specific mental health conditions.

Framing questions around stress, sleep, and coping strategies can make the conversation feel natural and supportive. Helpful approaches include:

Helpful approaches include:

- Normalize emotional reactions to chronic symptoms

- Explain the bidirectional link between tinnitus and mental health

- Encourage patients to describe how tinnitus affects their daily life

Example questions clinicians can ask:

- “How much is your tinnitus affecting your mood, sleep, or daily activities? Would you like me to connect you with someone who can provide additional support?”

- “Have you noticed any changes in your stress levels or emotions since your tinnitus started that you’d like to discuss?”

- “Many people find tinnitus can affect their mood or day-to-day life in ways they don’t expect. How has it been for you?”

Remember, our role isn’t to diagnose mental health conditions, but to screen, educate, and refer when needed.

Building Your Support Network

Before screening, it’s wise to establish referral pathways. Partner with psychologists familiar with CBT, counsellors experienced in chronic health conditions, and medical specialists for cases where medication may help. This ensures patients receive appropriate care and feel supported throughout their journey.

Why This Matters

When we integrate mental health awareness into tinnitus care, outcomes improve. Patients feel understood, better supported, and more empowered to manage their condition. For hearing care professionals, this isn’t about stepping outside our scope — it’s about practicing at the full scope of our profession and delivering care that meets the complex needs of our patients.

By looking below the surface of the iceberg, we not only treat tinnitus more effectively — we change lives.

If you found this blog helpful, please share it on social media!